Details

Contact

info@irishartscenter.org

Overview

Chapter 3

October 12, 2020-May 2, 2021

Series curator Darach Ó Séaghdha and artists Selkies, Eoin Whelehan, Amy Louise and Fiona McDonnell take us into the world of Irish mythology, with guest curators Fadilah Salawu and Ola Majekodunmi popping by for a spell.

For pronunciations, visit abair.tcd.ie/ga.

April 26-May 2

Illustration by Fiona McDonnell

The Irish word plámás means to flatter someone (or tell them what they want to hear) with a hidden motive. An example of plámás can be found in a well-known tale about a fox in the woods who spots a crow—a préachán (pray-khon)—on a tree branch with a piece of cheese in his beak. Realizing she cannot climb the tree, the fox instead tells the crow how beautiful a singing voice he must have, and would he be kind enough to sing for her. As the crow warbles away in his awful voice, the fox sneaks off with the fallen prize.

Crows are often presented as lazy, foolish and self-important elsewhere in Irish folklore, too, especially when compared to graceful birds of prey: cunning cuckoos, wise wrens, or industrious magpies. If someone were to wish "mallacht na bpréachán” ("the crow’s curse") on you, they are hoping that you abandon your work shortly before the fruits of your labour are finally achieved. The story goes that a crow’s nest is never finished…because they never shut up when they should be working.

This buffoonish reputation is slightly at odds with the role of the crow in the Táin, being one of the forms of the Morrigan war-goddess and landing on Cuchulainn’s shoulder at the moment of his death. However, the crow in that instance was referred to as badhbh (pronounced "byve") rather than a préachán.

April 19-25

Illustration by Fiona McDonnell

“An té nach bhfuil láidir ní folair dó a bheith glic” is an Irish proverb (seanfhocal) that means, “the one who is not strong is required to be shrewd.” The idea that people who appear puny on the surface are actually highly cunning is well-exemplified by the role of the wren—the king of all birds—in Irish folklore, with the best-known tale telling of how all the birds in the world decided to race to the sky to see who could fly highest. The winner would be declared king.

Rather than compete directly with its larger brethren, the wren hid inside the feathers of the eagle, resting during the ascent and hopping off to rise a few inches higher when the eagle could soar no more.

This avian trickster-king is associated with pre-Christian paganism in Ireland, famously for being the bird who snitched on Saint Stephen when he was hiding from the Romans, and inspiring the wren-boy events celebrated in certain parts of Ireland on the 26th of December (Saint Stephen’s Day). As part of the festivities, participants catch a wren (or make a fake one) in the morning and parade it around the locality while singing songs and requesting money from the houses they visit.

The Irish for wren, dreoilín, is derived from Old Irish—druí-én (“magic bird,” “druid bird”). It was believed that the number of times a wren bounced on a tree branch would predict how many soldiers would die in a battle fought that day.

April 12-18

Illustration by Fiona McDonnell

In Irish, the game of chess is called ficheall, which literally means "wood wisdom" (fid + ciall in Old Irish), and is taken from the name of an earlier board game played in Ireland that bears some similarities to its modern iteration. The game of ficheall appears many times in Irish and Welsh mythology: invented by the god Lú, played by Cuchulainn, and made a major plot point in the wooing of Etaine. There is even an incident in the Táin in which a hapless warrior is killed with a chess piece.

But what were the pieces called back then? The names we use now, such as king, queen and bishop, were added over time (the queen was previously known as “the vizier”) and do not always translate directly.

The knight in chess is called the ridire, the word used to refer to English and Anglo-Norman mounted soldiers in Irish history; it's still used today to refer to someone with a knighthood, such as “an Ridire Bob Geldof." It was not, however, the term used for Cuchulainn’s troop, the Red Branch Knights (laochra na Craoibhe Rua) or for the Fianna.

Other chess terms in Irish include ceithearnach (the pawn, literally a "yeoman" or "outlaw") and marbhsháinn (checkmate—literally "dead cornered").

March 29-April 4

Illustration by Fiona McDonnell

Draíocht can be associated with druidic art, druidism, witchcraft, magic, charm, or enchantment. It is "a ‘power’ or ‘talent’ attributed to the Tuatha Dé Danann in their ability to overcome the Fir Bolg, who preceded them in Ireland." (Oxford Dictionary: Celtic Mythology). Draíochtúil means magical.

In ancient times, Druids made up the higher-educated tier of Celtic society, including poets, doctors, and spiritual leaders.

For those looking for more draíochtúil vocabulary, you can visit Foclóir Draíochta—Druid Irish Dictionary, set up by Seán Ó Tuathail.

Guest-curated by Ola Majekodunmi.

Illustration by Fiona McDonnell, based on the Druids' brand of "magic" in ancient Ireland, in particular the ritual of cutting a sprig of mistletoe with a sickle & transforming others/themselves into animals.

March 22-28

Macasamhail means “reproduction,” “copy,” or “facsimile.” (A slightly uncanny thing if you look at in Freudian terms.) There is something uncomfortable about seeing a copy of a figure: be it a physical person like a doppelgänger or a shadow, it has the sense of a supernatural element to it.

Macasamhail can also have an association with the word “fetch” of Irish folklore: a supernatural double or an apparition of a living person. The sighting of a fetch can be regarded as an omen, usually of impending death. It is not a ghost, but a double of the person who has just died or is about to die.

“Fetch is also alluded to in the Old Norse mythology of fylgja. Fylgia is a supernatural spirit or an alter ego, usually in animal form, which is related to a person’s death. Fetch is also associated with the Old Irish term fáith, which means prophet. The idea of a fetch rose to prominence in the early 19th century, which was popularised in John and Michael Banim’s Gothic story, “The Fetches,” in Tales by the O’Hara Family.” (“Dublin Murders: What is a Fetch?”—Express.)

However, in Irish, there can be more regular meanings associated with macasamhail, such as leathchúpla (one half of a twin set), leathbhreac (half copy), comhchathair (sister city), comhbhaile (home), and seomra dhá leaba (two-bed room).

Gaois.ie says: "Bábóga i macasamhail daoine daonna amháin, lena n-áirítear páirteanna agus gabhálais díobh" ("Dolls representing only human beings, including parts and accessories thereof—human form, they are alike"). If you’ll notice, even in today’s popular scary films or stories, seeing or reading about a replica of something is meant to impart an eerie feeling.

You can also find replicas of Celtic-style swords and Cliamh Solais (the sword of light) on Pinterest if you are looking for Irish traditional objects.

Guest-curated by Ola Majekodunmi.

Illustration by Fiona McDonnell, who based her piece on the Sam Maguire cup from the GAA, which is a replica of an ancient Irish artifact known as the Ardagh chalice. The current-day Sam Maguire cup is also a replica of the original Sam Maguire cup from the 1920s; all three are depicted in this work.

March 15-21

Illustration by Fiona McDonnell

Taibhse (tie-v-sheh) means "ghost," "spirit," or "phantom." Many of us would have heard spooky stories with a taibhse in them, but what are the mythical origins of the word?

We are reminded of taibhse from Halloween or the Samhain festival (Oíche Shamhna or Oíche na Samhian as Gaeilge), which takes place on October 31 as a Celtic holiday, and on All Saints Day, November 1, as a Samhain tradition (Samhain being the Irish for November). Symbolizing the end of summer and start of winter, this is when nights begin to stretch out long, and spirits and ghosts are more likely to haunt their loved ones. The presence of a taibhse brings a rather sinister or supernatural presence: some of us imagine from movies that this phantom would scream out “boo” (like most kids do when they have on a white sheet, with three holes cut out, celebrating Samhain). There is also such a thing as a taibhseoir, a noun without a direct equivalent in English that describes a person who tells ghost stories. There is also the pooka (or púca, our Dec 21 Irish Word of the Week), the phantom horse who wandered the Irish night during the Samhain festival in pre-Christian times, and the banshee (the Dec 3 IWOTW), a female ghost who haunts the living when death is near.

Looking to read a book about a taibhse? Why not have a look at Taibhse Dá Thaobh: “There is a ghost on the loose in the local woodyard and it looks like it's not just a ghost – it’s a ghost that has been sliced in two! Sam keeps her cool, but Ben is all of a dither as they try to solve the case.” Check out siopaancarn.com.

Guest-curated by Ola Majekodunmi.

March 8-14

Illustration by Amy Louise

Wolfwalkers (2020) is the third movie in Tomm Moore’s Irish Folklore Trilogy (after The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea) and concerns conriochtaí—people who can take the form of wolves—in the time of Cromwell.

While werewolf myths are typically linked to curses that can only be broken by a purifying weapon (e.g., a silver bullet), this is not the case with the conriocht of Irish mythology, as illustrated in works including the 13th century poem "De hominibus qui se vertunt in lupos" ("Men Who Change Themselves into Wolves").

Wolves occupy a complex place in world mythology, ranging from classic fairytale villains (see: Little Red Riding Hood) to noble, family-oriented creatures who adopt human children lost in the forest (as in the story of Romulus and Remus, among others). Anthropologists still argue over whether people tamed wolves or wolves actually tamed early homo sapiens; either way, the contract between humans and dogs has outlived empires and continues to enrich our lives today.

The general Irish word for a wolf is faol, but the term Mac Tíre, which translates literally as "son of the countryside," is also used. This deference—just like referring to fairy folk as na Daoine Maithe ("the good people")—shows respect, but also a fear of provoking their force through speaking ill.

While the people of Ireland surely had confrontations with wolves over the centuries, their extinction on the island is directly associated with Cromwell’s campaign (they had been wiped out in England more than a century earlier), linking them to the notion of a lost pre-colonial past.

March 1-7

Illustration by Amy Louise

Is doiligh drochrud a mharú (it’s hard to kill a bad thing)—Irish proverb

The Bram Stoker Festival is celebrated in Dublin every year around Halloween. Cynics sometimes find fault with this timing, pointing out that Stoker showed little interest in Oíche Shamhna in his writings. In particular, he was more interested in a similar annual tradition which has since fallen by the wayside.

The novel Dracula begins with Jonathan Harker arriving in Transylvania on Saint George’s Eve, a night when all hell would break loose and evil spirits would run wild and free, much like the night before All Soul’s Day in Ireland. In Eastern Orthodox countries like Romania, the tradition was to put garlic on windowsills to protect households from bloodsucking creatures until Saint George, the dragon slayer, arrived and brought summer with him. Although Harker is an Englishman and fully familiar with the significance of Saint George, he does not realize that his feast day is different in the eastern church—not the last time in the story that things deviate sharply from his expectations.

Dracula remains Ireland’s most famous vampire, if not its most famous literary character altogether. However, there are others in Irish history, such as Abhartach in Derry and the Black Hag in Limerick.

Súmaireacht is the Irish verb for "sucking" (the spelling is tantalizingly close to súmhaireacht, which means "juiciness" or "succulence"). It is the root of súmaire, which describes a leech—but also a bloodsucking monster. And although the súmaire in Irish mythology is closer to our modern understanding of a zombie (it can also mean a slow, lethargic person), it's the word that was used when Stoker’s novel was translated into Irish in 1933 by Seán Ó Cuirrín.

February 22-28

Illustration by Amy Louise

The Irish for swan is eala. A place with many swans, such as the Coole Park of Yeats’ poem “The Wild Swans at Coole,” would be ealach: abounding in swans. Ealach can also describe someone or something swanlike.

Swans, like butterflies, are associated with dramatic transformation, as their recurrence in folklore reflects. Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake was first performed in 1877 in Moscow, and despite poor reviews and sales initially, it has gone on to become the most famous story of its kind: the transformation of a woman into a swan. Such tales are found throughout European folklore—"The Stolen Veil" in Bavaria, "The White Duck" in Russia, and the tale of glass mountain in Belgium are just some examples. And while a number of these stories are also found in Ireland and Scotland, the best known is the "Children of Lir."

King Lir, mourning his late wife, takes great comfort in his beloved children: Fionnghuala, Aodh, Fiachra, and Conn. His new spouse, Aoife, in the classic wicked stepmother tradition, is jealous of their loving bond and conspires to remove them from the equation. Upon taking advice that they cannot be killed, she chooses the next best thing and turns them temporarily into swans. In this instance, however, "temporarily" means nine hundred years.

"Children of Lir" differs from many other swan-transformation stories in that the version that has survived includes a Christian element that was certainly added after the fact: the swans are turned back into (nine-hundred-year-old) human form by church bells, and are baptized right before they die. The fact that three of the four children are boys is also unusual in tales of this kind.

So loved is this story that statues of swans can be found today near the bodies of water mentioned in it—Loch Dairbhreach in Westmeath, Inis Gluaire in Mayo, and Sruth na Maoilé in Antrim.

February 15-21

Illustration by Amy Louise

“Never write a letter and never destroy one” is a quote that is sometimes attributed to Cardinal Richelieu, and sometimes to the character Mephistopheles in the legend of Faust. The fact that this line has multiple possible origins—and that those origins include a real historical figure who is also the villain in a popular series of novels as well as a character in a tale with differing versions—underlines the wisdom of its central point: that the inclusion or exclusion of a single piece of evidence can entirely change our understanding of an event, person, or idea.

A common situation in which this applies is when a word is listed in an old dictionary but not found in surviving texts from the same period. Bibsach, for example.

The Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of the Irish Language (the DIL, for short) defines bibsach as “killing or to put to death twice.” However, the entry is marked with a question mark to warn the reader that it has been flagged as a possible ghost word, a term lexicographers use to describe words only found in dictionaries. Sometimes these are typos or misunderstandings, as was the case with ‘syllabus’ and ‘tweed,’ both of which caught on with English speakers. But others never gain the legitimacy that comes from widespread use, and survive only to torture students.

The source cited for bibsach in the DIL is De Origine Scoticae Linguae, better known as O'Mulconry's Glossary, a text from the 7th century (earlier than the Book of Kells). This period of history is to what “the island of saints and scholars” refers, when significant scientific research in multiple languages was being conducted by Irish monks. O'Mulconry's Glossary is regarded as a milestone in European history, being the earliest etymological study of a vernacular language, presenting origins for nearly 900 Irish words from Hebrew, Latin, and Greek dialects. However, it is unclear where it was used, if ever, prior.

Could bibsach have been a reference to a legal concept in Brehon Law akin to double indemnity? Or is it from a story (and there are many in mythology) in which something had to be killed twice? Some horrible event that the survivors wanted to make sure was never remembered? Or…is it just a mistake in some teenage monk’s homework from over a thousand years ago that got included in a 20th century dictionary by accident?

The good news is that although history happened long ago, its exploration is ongoing. A new version of O'Mulconry's Glossary was published in 2019; continued examination of this word and this period in time may yet reveal an explanation far less entertaining than the speculation such a darkly mysterious word inevitably invites.

February 8-14

Illustration by Amy Louise

In pre-Christian times, Ireland was so covered in trees that it was faster for people in Ulster to reach the islands off the coast of Scotland by boat, than to travel far shorter distances by land. (At one point, the kingdom of Dál Riada comprised the northeast of Ireland and the southwest of Scotland.) This might be a factor in how these islands appear often in the poetry and mythology of the region.

The Isle of Skye (an tEilean Sgitheanach), on Scotland’s west coast, features in the story of Cú Chulainn and his foster-brother Ferdiad. In order for Cú Chulainn to win the hand of Emer, her father insists he must train to be a warrior, so he decides to go to Skye to study under the legendary female warrior Scáthach. Her reputation as a martial artist is great, as is her precondition for accepting students: only those who can successfully infiltrate her island fortress will be considered.

Although she trains both foster brothers in the same way, Scáthach gives only Cú Chulainn a magic spear—called the Gáe Bulga—and instructs him on its proper use. Years later, when fighting one another, Ferdiad and Cú Chulainn are equally matched, but Cú Chulainn's possession of this spear decides his victory.

As well as being the name of this warrior queen, scáthach can also mean 'shadowy' or 'sheltered.' There are structures still standing on the Isle of Skye today named after Scáthach and Cú Chulainn.

February 1-7

Illustration by Amy Louise

One of the most famous figures in Norse mythology, a valkyrie is a female demon who flies over battlefields, choosing which of the slain had fought bravely enough to be taken to Valhalla to dine with Odin (the others would have to settle for Fólkvangr). It is a powerful image, commemorated in the best known segment of Wagner’s Ring cycle: "Die Walküre" ("Ride of the Valkries").

Inevitably, the idea of male warriors getting rewarded for their cause by supernatural, beautiful women after dying is terribly attractive to propagandists.

However, this may not have been the original intent of the allegory, as similar figures in neighboring mythologies suggest. In the battle scenes in Táin Bó Cúailnge, the skies are described as being full of demons with an unknown interest in the outcome. These are listed in the same order: bánanach (white demons), bocanach (goat-like demons), ginid glinne (demons of the glens), and deamhan aeir (air demons). All these creatures are presented as malevolent, more scavengers than war angels. And while in the Táin, warriors do worry about whether they'll die on their back or front in battle (indicating whether they were brave or cowardly), this theme is unconnected from the presence of the demons in the story.

Rather than taking fallen warriors on the “right side" to glory, the motive of the bánanach and their brethren is to delight in conflict itself.

January 18-31

Intermission

January 11-17

Snaidhm seirce: love knot

Snaidhm (pronounced snyme) means a knot or a bond.

Seirce (pronounced sure-kah) is a grammatical form of searc (pronounced similarly to shark), meaning darling or beloved.

Tying the knot—a euphemism for getting married—alludes to the old Irish and Scottish tradition of handfasting. Some Irish couples still observe handfasting today, tying a knot in a rope upon wedding and adding a new knot for every child to join the family. Shakespeare even refers to the ritual in Romeo and Juliet.

A love knot of a kind also features in Roscommon’s own tragic tale of Úna Bhán (Fair Úna) and Tomás Láidir (Strong Tom). Though burly, handsome and charming, Tomás Láidir is penniless, so when he wins the heart of Úna Bhán—the daughter of a local chieftain—her father opposes the match, banishing Tomás from the kingdom and locking up his daughter in an island tower. When Tomás attempts to reach her, he's tricked into believing she wants nothing more to do with him, while she dies of a broken heart. Every night thereafter Tomás flouts the banishment order and swims to the island to be at her graveside. Eventually catching and succumbing to pneumonia, his dying wish is to be buried next to his beloved, a request her grieving father cannot deny.

It is said that years later, two trees grow from these graves, their branches entwined in a love knot.

This cheerful story reminds us of the terrible consequences of the misuse of power and the folly of standing in the way of true love.

Illustration by Eoin Whelehan, who adds a Rapunzel-esque twist to the story of Úna Bhán and Tomás Láidir: Úna's flowing hair forms a knot beneath the lovers in a fleeting reprieve from their fate.

January 4-10

Illustration by Eoin Whelehan

January 6 is the feast day of Nollaig na mBan—Women’s Christmas, traditionally when women in Ireland, exhausted after the events of Christmastime, get to put their feet up and be waited upon by the men and boys of the family. While such respite is welcome, it is unfortunately born from the belief that certain household labor is determined by gender. But were gender roles, and the idea of gender itself, always so fixed in Irish society?

The curious tale of the abbot of Drimnagh tells of an Easter evening back in the mists of time, when the abbot in question falls asleep by a hillside after a long walk. Upon waking, he finds himself transformed into a woman. She, on her way home, crosses paths with a handsome man—a senior monk at the abbey in Crumlin—and the couple later wed and have children.

The word used in the original text to describe the abbot's transition—aitherrach—literally means "a new springtime." The modern spelling is athrach.

December 21-27

Illustration by Eoin Whelehan

Many Irish schoolchildren are taught that the púca (poo-ka) is of the same species as the common white-sheet ghost—but its true identity is far more interesting and complex.

Described as shape-shifters who can take the form of horses, dogs, hares and other animals, púcaí (plural) are commonly understood to be goblins or demons, feared for bringing ill fortune to those who come across them—although good púcaí are said to exist, too. These mischievous creatures are known to scare and confuse humans, especially with their gift of human speech, which they use to spin long tales that entrance the listener.

Another trope of the púca is, when in the shape of a horse, their taking humans on wild and terrifying rides in the dead of night, often when the rider is drunk.

The place name Poulaphouca, meaning “the hole (or den) of the púca,” was historically given to many areas of Ireland said to house the creatures.

The púca is common across various Celtic traditions, with Welsh, Cornish and Celtic French lore having similarly-described creatures, albeit with regional variations.

Guest-curated by Fadilah Salawu.

December 14-20

The mythical “Land of the Young” is the setting of one of the most well-known and classic Irish folktales: the story of Oisín and Niamh Chinn Óir (literally “blonde/golden-headed” Niamh).

As with any folktale, there are many versions of the story, but the general series of events is this: Oisín, a strong, charming and respected warrior of the Fianna tribe, is visited one day by the mysterious, beautiful, and regal Niamh (a spéirbhean) on horseback, who asks him to marry her. She tells him about the Land of the Young and proposes he move there with her, to live forever in the bliss of eternal youth. He agrees, bidding farewell to his tribesmen to start a new life in Tír na nÓg.

(In some versions, he slays a few monsters and saves a damsel in distress along the way.)

Tír na nÓg turns out to be as wonderful as he’d imagined, a paradise full of health, riches, beauty and peace, and initially he is pleased with his life there with Niamh and the children they have. Eventually, however, he begins to miss Ireland and the Fianna, and decides to pay a visit home. Niamh agrees to this trip and gives him a horse, but not without the warning that although he hadn’t aged in Tír na nÓg, time in the ordinary realm had continued to pass, and should he set foot on ground, his human age would reflect immediately and his youth would be lost.

When Oisín arrives back in Ireland, he learns that the Fianna are long dead, much to his disbelief, and finds in their place a group of young men trying to move a large boulder. In helping them in their effort, Oísin falls off his horse and, upon hitting the ground, becomes a weak, blind old man.

Depending on the version, he either dies at this point or becomes an acquaintance of St. Patrick’s, with whom he travels to spread the word of Christianity.

Illustration, by Eoin Whelehan, is representative of Iron Age imagery. The horseshoe represents Oisín, which in turn represents the boat of Manannán mac Lir (“son of the sea”). The design also incorporates sections of W.B. Yeats’ “The Wanderings of Oisin”—the silver apples of the moon, the land of milk and honey, and the setting sun.

Guest-curated by Fadilah Salawu.

December 7-13

Illustration by Eoin Whelehan

Many loud noises (and children) are often compared to the mythical banshee, from the Irish bean sí ("woman of the mounds"), which refers to the hills (sí) of the Irish countryside in which banshees are said to reside.

Also translated as "woman of the fairies" due to her other-worldliness, and commonly known as a wailing spirit, the banshee appears in many forms, ranging from a sweet young woman to a haggard old lady described as long-haired, pale and ghostly with eyes red from crying, wearing long robes and a sorrowful countenance.

She is known for wailing and shrieking in mourning for a dead family member, and is also sighted by those soon to pass as an omen of death. In some instances, her appearances signify a warning to avoid a fatal situation.

Banshees wander not only through the countryside at night, but through the folklore of different cultures. They appear similarly in the Welsh and Scottish traditions, and as far away as Mexico, where the tale of "La Llorona" shares the theme of a wailing woman in mourning, albeit for different reasons. The English word "keening" comes from the Irish caoineadh, which means to weep or wail, which is why a banshee is also known as a bean chaointe, or weeping woman.

Guest-curated by Fadilah Salawu.

November 30-December 6

Illustration by Eoin Whelehan, inspired by figures on the west face of the South Cross, a 9th century monument in County Meath.

A recurring theme in mythologies around the world is the ability of a good king to solve an impossible riddle—revealing truth by asking questions that hit at the heart of the matter.

One such example found in Irish lore is the story of Niall Frossach, recalled in the Book of Leinster. A young mother comes to King Niall's court and asks if he can determine the father of her infant son, explaining that she has not had relations with a man in some time. (Intriguingly, she refers to such relations as “guilt.”) Pondering the matter, the king asks if she has enjoyed lanamnas rebartha ("playful mating") with a woman in the time before her son's birth. When she confirms that indeed she had, the king concludes: her woman lover had recently been with a man, and his seed—still on her body during the playful mating (which he also refers to as “tumbling”)—was transferred to the young mother. Upon this judgment, a priest who'd been trapped in the sky by demons falls safely to the ground—the power of truth in Niall's words freed him from his curse. He compliments the king on an excellent verdict.

This tale gives a fascinating insight into how same-sex relations were viewed in Ireland in the 12th century, especially with regard to how an encounter between a woman and a man is referred to as "guilt," but an encounter between two women is "tumbling" or "playful mating."

The modern spelling of "playful" is reabhradh.

November 16-22

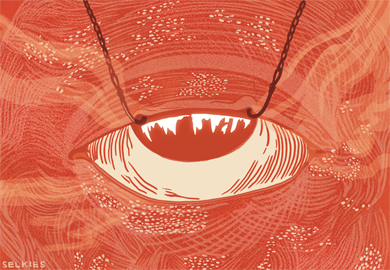

Illustration by Selkies. For a closer view, click the photo top left of page and scroll right.

It’s been said that the tale of Icarus, with its emphasis on invention and cautions about the limits and perils of technology, is the first ever science fiction story. Around the same time of its genesis (give or take a century or two), the first tellers of Irish myths were also using the narrative techniques science fiction writers would employ in our time—flying saucers, robot arms, and weapons of such power that their safe keeping became a bigger problem than the external enemies they are supposed to protect against.

Take Balor. Balor was an evil giant who lived on Tory Island, a cliffy promontory off the coast of Donegal that was the edge of the known world as far as these first storytellers were concerned. Balor had the drochshúil—evil eye—that fired poisonous laser beams at his enemies, like something out of science fiction. After hearing a prophecy that he would be killed by his grandson, he arranged for his daughter to be locked in a tower. This scheme did not work (does it ever?): years later, the demigod Lúgh (pronounced "Looh") slayed Balor with a slingshot and used his severed head as a weapon by manipulating the eyelid manually.

Droch: evil or bad

Súil: eye

With its own evil-eyed monster (like the Cyclops) and the phenomenon of using severed heads as weapons (see: Medusa), it seems Irish mythology arrived at a similar moment to the mythology of Ancient Greece, even though developed a world away.

More recently, the figure of Balor, or versions of him, have turned up in Dungeons & Dragons, computer games, comics, and even wrestling (Finn Balor).

To hear how drochshúil is pronounced, visit abair.tcd.ie/ga.

November 9-15

Illustration by Selkies. For a closer view, click the photo top left of page and scroll right.

In Brehon Law, a woman slave (cumhal) was valued at three cows or three ounces of silver, according to Fergus Kelly, author of the most definitive book on the subject. But what happens when the cumal (pronounced "cuh-well") is actually a princess in disguise?

The Icelandic saga Landnámabok is not well known in Ireland, though it speaks to the historical connection shared by the two islands. A number of place names in Iceland hint at an Irish link—Kjaransvik (Ciaran’s Bay), Irafellsbunga (Mountain of the Irish) and Vestmannaeyjar (the Westman Islands, "west men" being a Norse name for the Irish)—indicate a significant amount of migration. But were these migrants travelling of their own will?

The capture of Irish women and girls by Icelandic slavers has a legacy in genetics: up to 70% of mitochondrial DNA (carried on the mother’s side) in Iceland can be traced back to Ireland. The phenomenon is noted in Icelandic mythology, too.

In the story of Melkorka, an Irish princess carried to Iceland as a slave, Melkorka refused to speak to her captors, leading them to assume she was mute. She broke her silence when she bore her son, Olaf, speaking to him in Irish, and encouraging him to journey widely and be the author of his own destiny, rather than to do what his father told him.

Years later, when travelling to Ireland as a merchant, Olaf impressed the hostile locals—and saved the lives of his fellow sailors—by speaking to them in perfect Irish. When he was brought to meet the local high king, the king recognized the ring Olaf bore—a ring given to him by his mother, who had received it from her father—and realized his grandson was before him.

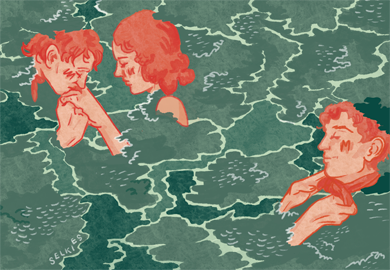

November 2-8

Illustration by Selkies. For a closer view, click the photo top left of page and scroll right.

Spéirbhean (pronounced spare-van) translates literally as “sky woman,” or “woman of the heavens.”

The best-known genre of poetry in the Irish language is the aisling: a vision within a dream, in which the narrator falls asleep and a beautiful woman appears to them. For example, in the poem “Ceo Draíochta” (“The Magic Mist”), the spéirbhean is described as síorshileadh (ever-weeping) and righinrosc (languid-eyed), with hair that is buí-chasta (literally “yellow-twisting”: long, blonde curls tied in a fabulously stylish way).

She laments the predicament in which Ireland finds itself (this style of poetry was most popular in the aftermath of Cromwell’s invasion), and the conclusion is a plea for—or a prediction of—a significant athrú réimis (change in regime).

The aisling genre became a victim of its own success and was satirized in later works like the “Cúirt an Mhéan Oíche,” in which the spéirbhean is a terrifying giant.

October 26-November 1

Illustration by Selkies. For a closer view, click the photo top left of page and scroll right.

“Tóraíocht Diarmuid agus Gráinne” is a tale of two runaways: Gráinne is engaged to be wed to the much older Fionn MacCool; Diarmuid is his loyal, young lieutenant whom she falls for and runs away with. They are chased around Ireland by Fionn (tóraíocht means pursuit), a hero in other Irish legends but very much the villain here. Ireland’s map is studded with what are said to have been temporary resting places for the fleeing couple.

In the early 1900s, this story was turned into a play by Lady Gregory, despite warnings from friends that the endeavor might be too revealing: Gregory herself was to marry a much older man—Lord Gregory, a Tory politician—but truly in love with the young poet, adventurer, and political radical Wilfred Scawen Blunt.

(Curiously, the British Conservative party nickname, the Tories, comes from the Irish word tóraí, meaning a bandit or outlaw, which itself is derived from tóraíocht. This could be translated to: the Tories are involved in an illicit pursuit, or are themselves being pursued.)

Since then, “Tóraíocht Diarmuid agus Gráinne” has gone on to be one of Ireland’s best-loved myths (though perhaps not by the teenagers made to study it in school), and both Diarmuid and Gráinne are enduringly popular children’s names.

October 19-25

Illustration by Selkies. For a closer view, click the photo top left of page and scroll right.

A tochmarc (modern spelling: tochmharc) is a tale of courtship from Irish mythology, recounting how the path of true love never runs smoothly, even among the supernaturally gifted. It is a combination of the Old Irish words tocraid (modern spelling togair, meaning “desire”) and marc (“target”).

These tales are similar in some ways to Arthurian romances, in how they illustrate the seemingly impossible hurdles faced by those in pursuit of love. The “Tochmarc Etaine” tells how the most beautiful woman in Ireland, Etain, is pursued by Eochu, a high king. However, she is the reincarnation of the woman who Midir (a supernatural prince, one of the Tuatha Dé Danaan) had been in love with, and who is still intent on pursuing her. To complicate matters, Eochu’s own brother is also in love with her.

Another story, “Tochmarc Emire,” tells the story of how Cúchulainn and his wife Emer got together. After initially meeting and flirting by exchanging double-meanings, they fall in love. However, Emer’s father, Forgall, disapproves of the match. He proposes that Cúchulainn go to Scotland to train as a soldier under the tutelage of the legendary woman warrior Scathach, assuming he won’t survive this test. Meanwhile, he tries to arrange a marriage for Emer to someone else. Of course, this plan backfires horribly—Cúchulainn comes back more skilled and dangerous than ever, and storms Forgall’s palace to rescue his love.

October 12-18

Illustration by Selkies. For a closer view, click the photo top left of page and scroll right.

The idea of transformation is a recurring one in world mythology: it presents as a fear, a wish, or a combination of both. This theme is present throughout the Irish epic the Táin, particularly with regard to Cúchulainn, who would enter warp spasms—referred to as ríastrad in the original text—in battle.

Ríastáil can mean "turning sods of turf" (revealing their other side), but can also refer to severe laceration. Both meanings are apt in the context of Cúchulainn’s body’s violent contortions.

In the Táin we are told he “made a terrible, many-shaped, wonderful, unheard of thing of himself”: his hair became spikes, his jaw extended, and his limbs contorted until he was a fierce creature. The idea of Cúchulainn’s becoming a battle monster echoes the story of how he got his name—literally, the Hound of Culann—when he promised to become Culann the Smith’s guard dog.

Some academics have argued that this transformation makes Cúchulainn a forerunner of modern superheroes; others claim that by leaving his human state in battle, the original storyteller is explaining why the codes of behavior expected of an Irish warrior at the time do not apply to him.

There are several English translations of the Táin, including versions by well-known poets like Ciaran Carson and Thomas Kinsella.

Click here for Chapter 1 >

Click here for Chapter 2 >